Culture

Bhutan has long maintained a policy of strict isolationism culturally and has relied on its geographic isolation to protect itself from outside cultural influences. With the goal of preserving its cultural heritage and independence, only in the last decades of the 20th century were foreigners are allowed to visit the country, and only then in limited numbers. In this way, Bhutan has successfully preserved many aspects of culture, which dates directly back to the mid-17th century.

People & Language

Bhutan has the lowest population density of any country in south Asia. And most people live along the southern border and in the high valleys of the mid-mountain belt, particularly along the east west trade route that passes through Thimphu and Punakha. There are two main population groups in Bhutan: The Drukpa which is approximately 77% of Tibetan and Monpa Origin, who inhabit the mid-Mountain belt, and the Lhosthampa which is approximately 20% of Nepalese origin, who inhabits the southern borderlands. The remaining 3% of the population comprise indigenous tribal groups, such as the Toktop, Doya and Lepcha of the south-west Bhutan, and the Santal who migrated there from northern Bihar. All together 19 languages and dialects are spoken in Bhutan. Among the two larger groups, the Drukpa include within their numbers speakers of eight indigenous Tibetan dialects, which have been identified by the linguist George van Driem, including the dominant Ngalong of western Bhutan who speak the dialect now known as Dzongkha, the official national language and many other Tibetan dialects are spoken in remote parts of the country. Monpa is the other classification of Drukpa people of Wangdi Phodrang, Zemgang, Trongsa and Bumthang districts, who speaks an east bodish Tibeto- Burman language, somewhat related to dialects spoken by the Monpa’s of tawang based in Arunachal Pradesh. Finally the most popular group is the Sharchokpa of eastern Bhutan, who have been identified as Lopas, speaking Tibetan-Burman language known as Tsangla.

Dress

The national dress of Bhutan accords with the conventions of the official code of conduct which was established by Tenzin Drugye, the first regent of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in the 17th century. Like tha traditional dress chuba worn by the neighbouring Tibetans of Dromo, Khanmar and Lhadak, Bhutanese dress is influenced by the harshness of Himalayan climate apart from other important differences. The national dress depicts one of the most distinctive features of the Bhutanese identity. Men wear Gho, hitched up to the knees with sash which causes it to form a pouch above the waist and a long –sleeved shirt, with a cuffs turned back. The pouch which forms at the front traditionally was used to carry food bowls and a small dagger. Today it is more a customised to carrying wallets, mobile phones and Doma (beetle nut). Women wear the Kira, a long, ankle length dress accompanied by a light outer jacket known as a Tego with an inner layer known as a Wonju, and then wrapped around to be fastened at the shoulders with two sliver brooches. A tightly fitting waist belt of silver or woven cloth forms a pouch in the upper garment, similar to the pouch of Gho. The wearing of the national dresses is compulsory for school students, government officials. Also while attending formal meetings or entering a Dzong.

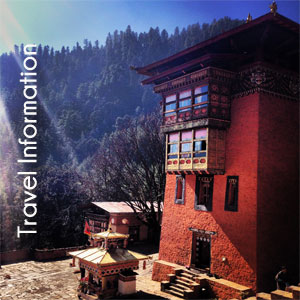

Architecture and traditional living

Traditional architecture varies according to the region. In the southern border areas and in parts of eastern Bhutan thatched bamboo houses are constructed on stilts, which offer protection from floods during the rainy season and from unwelcome insects or reptiles. In the Laya and Lhinzhi areas of northern Bhutan, as well as some parts of central Bhutan, villages characteristically comprise a number of flat-roofed stone dwellings, while the nomads of that area, like the nomads of neighbouring Tibet, live in black yak-tweed tents. The most typical Bhutanese style of architecture are seen in the mid-mountain belt, the houses are shingled, with slopping roofs, similar to dwellings in the Kongpo area of southern Tibet, and the thick walls are found made of compacted mud, constructed of intricately carved timbers, forming a series of shuttered windows. The lower floor of village houses is normally used for storage and for animals and the family occupies the upper storey; access to the upper storey is made by scaling a notched “tree-trunk” ladder of the type that is still found in many parts of the Tibet, where the interior walls are bamboo lattics plaster with mud. The attic is used as a drying area during the harvest season. The outer walls of the houses are frequently white washed, contrasting with a richly painted woodwork. Sacred motifs, such as the eight auspicious symbols are common place and the exterior of the door is likely to depict a Garuda, tiger or enlarged red phallus- said to distract and ward off malevolent forces. Oil lambs were used for lighting once but now it’s provided with kerosene and electricity. More distinctive than village architecture is the magnificence fortress found over many strategic locations overlooking the town in almost all the districts, such monasteries comprises of flag stoned courtyard leading to a central assembly hall which contains many chapels within it, Surrounded by many out buildings of a kitchen, sleeping quarters for monks, a hermitage and some stupas. Larger monasteries may have freestanding temples and specialist colleges outside the main building.

Food and eating habits

Bhutanese cuisine for the most part is pretty basic. In the central hills of Bhutan, red rice is the staple, eaten with spicy and hot vegetables and meat curries. The national dish emadatsi consists of hot chillies and melted cheese, served with rice. Other spicy alternatives include beef with spinach, pork with rice noodles, and chicken in garlic butter. Pork and beef are the most commonly available meats. Buckwheat pancakes and noodles are popular in the Bumthang area, corn in Trasigang and roasted barley or wheat in a nomadic drokpa area of the northern mountains. The nomads also have Yak meat which is favourite in the winter seasons, some mutton and dairy products- yoghurt, butter, milk, buttermilk, as well as cheese in many varieties. Roasted barley is also a staple of Tibetan diet. Apart from other Tibetan dishes the famous Momo, country-style noodles, and noodle soups are great favourites. In the south of Bhutan Nepalese cuisine is predominant and some Nepalese dishes such as dhal bhat (rice & lentils) and alu tikari (potato curry) can be found in restaurants throughout Bhutan. Vegetarian fare is widely available and exotic: nettles, asparagus, taro, orchids and various types of mushrooms are found. Desserts are not generally served but delicious apples, apricots, peaches, and walnuts are available in season. The Indian habit of chewing paan or doma(a misture of powdered lime, palm nuts rolled up iin a betel leaf) is widespread. This habit is discouraged because of the links paan and oral cancer, also the red stains left on the pavements where paan eaters have spat out the remains are considered unseemly.

Traditional eating habits are simple and in general food is eaten with hands. Family members eat while sitting cross legged on the wooden floor with food first being served to the head of the family. The mother usually serves the food and a short prayer is offered before eating. Dishes are cooked in earthenware, but with modernisation eating habits have changed in urban areas, people usually eat cutlery whilst seated at a regular dining table and modern goods have largely replaced earthenware.

Bhutan Travel Info

Bhutan Travel tips, Daily Tourist Tariff, Bhutan Visa Information, Tour payment regarding your tour booking to Bhutan. Click on the link below to know more.

Learn more >>

Tour Packages

Travel to Bhutan with Sachock Bhutan Travels. We, at Sachock offers Cultural tours, Trekking Tours including the World's toughest Trek Snowmen Trek and colorful Festival tours of Bhutan.

Learn more >>

Getting into Bhutan

Travelling to Bhutan can be accessible by Air, to Paro(the only international airport in Bhutan connecting with Indian Cities, Nepal, Bangaldesh, Thailand & Singapore) & Road through Southern border towns of Phuentsholing, Gelephug and Samdrup Jongkhar.

Learn more >>

Sachock Bhutan Travels, P.O Box No: 1304, Karma Khangzang, Thimphu : Bhutan

Phone # (+975) 77177717 / 77210443 : Tele-Fax (+975) 2 333 881

Email: [email protected] / www.SachockBhutanTravels.com

Sachock Bhutan Travels, Copyright © 2025. All Rights Reserved.